A silent disaster is gripping the world’s young people. It rarely makes global headlines but its consequences are every bit as ruinous as the stories that do.

Hundreds of millions of children are not learning. They are not reaching even basic standards in literacy and numeracy. The World Bank estimates that 70% of 10-year-olds in low and middle income countries cannot read and understand a simple text. In sub-Saharan Africa, that figure is 90%.

UNESCO acknowledges that SDG4 – the Sustainable Development Goal due to deliver quality education to everyone by 2030 – will be missed. Its most recent update says:

“By 2030, according to countries’ own benchmarks, out of a cohort of 800 million children of primary school age, 37% or more than 300 million children will not be completing primary school and reaching the minimum learning proficiency in reading by that stage.”

This, despite a largely successful battle to ensure all children attend at least primary school.

UNESCO estimates 90% of primary age children attend school. By 2030 it expects that figure to rise to 98%. 85% complete primary school, rising to 94% by 2030.

The fight being lost is to ensure that children in school are actually learning. But it does not have to be.

As Dr. Benjamin Piper, Director of Global Education, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, says:

“We have solutions that can work at scale and in government systems. Committing to substantial learning recovery programs is a start, but the composition of those programs matter: measure learning outcomes, but also invest in improving instruction through structured pedagogy or teaching at the right level.”

A major new study by a group of US academics led by the Nobel Prize winning economist Professor Michael Kremer, has examined just such a solution.

Its findings are startlingly clear.

“The test score effects in this study are among the largest observed in the international education literature, particularly for a program that was already operating at scale, exceeding the 99th percentile of treatment effects of large-scale education interventions reviewed by Evans and Yuan (2020).”

It’s worth stressing what that means. A learning program, working at scale in Africa, has been confirmed through a rigorous independent study to deliver learning gains which are much bigger than virtually any studied before.

Professor Kremer and his co-authors, Guthrie Gray-Lobe, Anthony Keats, Isaac Mbiti and Owen Ozier examined the benefits of a structured and standardized approach to teaching and learning.

The study of schools in NewGlobe’s Bridge Kenya program was conducted over two school years and included more than 10,000 students from lower socio-economic backgrounds.

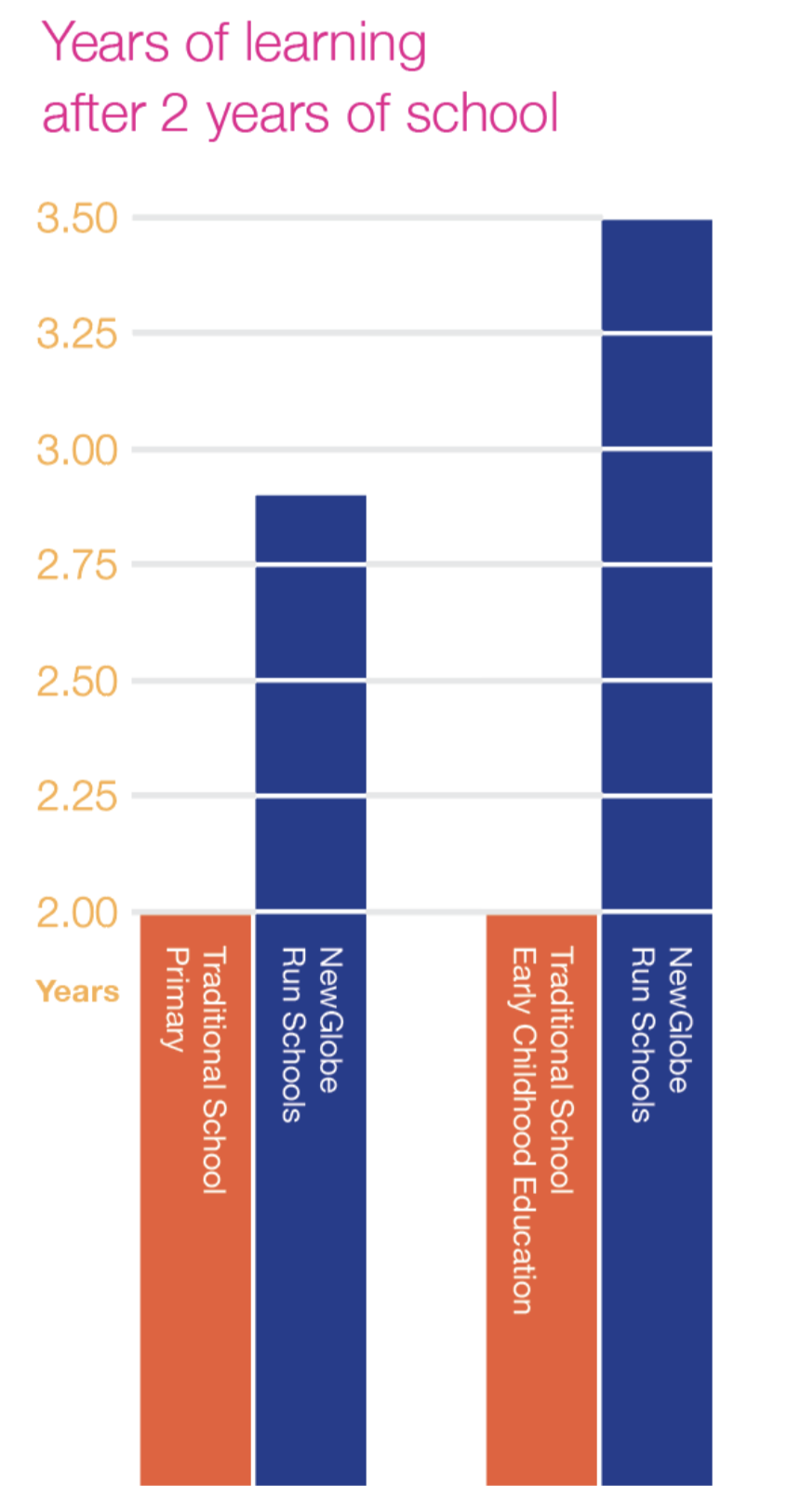

It finds primary students through Grade 8 gain almost an additional year of learning (0.89) under the NewGlobe integrated methodology, learning in two years what their peers learn in nearly three.

For early childhood development (ECD) students the gains are even bigger. Those students supported by NewGlobe gain almost an additional year and half of learning (1.48), learning in two years what students in other schools learn in three and a half years.

By Grade One, aged six or seven, more than 80% of students were reading – three times the number in other schools.

The Kremer et al. study analyzed a methodology that is data-rich, includes a digital learning platform, adaptive instructional content, professional development, and 360 degree support.

A focus on school management combines with the use of cellular networks to ensure each school leader has purpose-built applications for school management and instructional leadership, as well as to digitally publish teachers’ lesson guides and supporting materials.

By digitizing materials and information systems, NewGlobe makes core activities within each supported school and classroom visible, and uses that data to support decisions made on everything from the deployment of field support staff to lesson design.

Professor Kremer and his co-authors are clear on the implications:

“This study shows that attending schools delivering highly standardized education has the potential to produce dramatic learning gains at scale, suggesting that policymakers may wish to explore incorporation of standardization, including standardized lesson plans and teacher feedback and monitoring, in their own systems.”

Pioneered in Kenya, this integrated approach to teaching and learning has been embraced by governments in countries including Nigeria, Rwanda, India and Liberia. The World Bank is noticing the results and supplying additional support – as in the case of the EdoBEST program in Nigeria’s Edo State.

One million students – 95% in public schools – are being taught using the methodology in this groundbreaking study, and the figure is increasing year on year.

As Benjamin Piper says, there are solutions to the global learning crisis which work at scale, and in government programs. The challenge now is to focus on implementing them and turning around the appalling learning outcomes blighting the lives of so many.