Born in 2010, Faris is considered to be a digitally native child who will never experience a world that is untouched by the digital age. The world that he is brought up in differs drastically from that of his parents. Faris will never experience a world that is without internet, smartphones or computers. Whereas his parents have experienced a life before and a life after the widespread adoption of digital technology. These generational differences must be taken into consideration to better inform the ways to impactfully educate Faris and his peers.

Arabic literacy education has been affected by two major characteristics:

Characteristics of Today’s World

Digital World

A Common Sense Media study shows that today’s youth have tripled their screen-time (from 15 minutes in 2013 to 48 minutes today). It also shows that children at the age of eight and below are spending 35% of their screen time on mobile devices in 2017, in comparison to 2013 when it was only 4%. Since 42% of these children have their own tablets, technology consumption is higher.

Consequently, this rapid increase in using electronic devices will inevitably influence the way children learn. Online games can engage children and capture their attention for long hours, since they are designed with children’s interests in mind. Moreover, children are exposed to many options when it comes to digital educational content. Consequently, this poses an inevitable challenge on traditional classrooms and how they engage their students, particularly if these classrooms lack digital and/or interactive content to supports local curriculum.

Multilingualism

Exposure to other languages

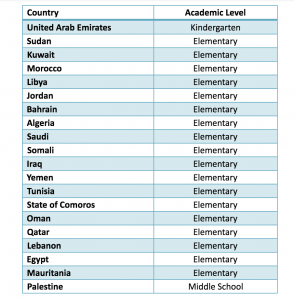

The number of bilingual speakers is increasing; especially in USA and Europe. Arab children are experiencing similar trend as they live in a multilingual world and are exposed to second languages from a young age. As Table 1 shows, 90% of countries in MENA region start introducing a second language as early as elementary school. Since some schools in the region teach Arabic as a second language for native speakers, this indicates that these children are familiar with at least one other language.

Table 1: Arab Countries and Academic Level

When Introducing Foreign Languages

Arabic as a Second Language

There is a significant Arab displaced population in the Western world, where Arab-origin immigrants practice Arabic as a second language. For example, in Canada there are 419,890 people whose “mother tongue” is identified to be Arabic while only 223,540 speak Arabic at home— of which the children are formally learning and practicing Arabic only once a week.

Moreover, non-native speakers seeking to learn Arabic as a second language are increasing due to multiple trends, such as: (1) Muslims represent over 24% of world population and Islam’s growth is expected to keep rising, hence more interest in achieving Arabic proficiency to read the Qu’ran. (2) Arabic subject is being added as part of few western countries’ public schools, such as in Edmonton – Canada and UK.

Arabic as a Mother Language

It is important to mention that Arabic is a diglossic language, which means that native learners are expected to learn two forms of the language; Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and colloquial one. To elaborate, for the first 4-5 years of children’s lives, they are mainly exposed to colloquial Arabic. When they start school, they are taught in Modern Standard Arabic, which is quite different than the familiar, colloquial language they have been communicating with. This difference can confuse children and cause them a cultural conflict. When kindergarten teachers were asked about this phenomenon, they affirmed that this conflict hinders children’s ability to comfortably learn Arabic.

Current Measures for Modern Challenges

Currently, cartoons and TV shows have been used to expose children to MSA before they get to school in an attempt to bridge this gap. However, there are varying opinions about the effectiveness of this methodology. Moreover, eduTechnoz studies have shown an increase in grades of 34% when students used its curriculum-mapped digital games for 20 minutes per week.

While using digital games and media can help, we still need a radical solution that is suitable for all the participants in this educational process. Arabic literacy education needs to refocus its attention from increasing grades to nurturing life-long readers who appreciate the wealth of Arabic language; we need to #Innovate_Reading_Learning_Process.

This article lays the contextual foundation for next piece in this five part series. The next article will expand on the challenges facing Arabic literacy education. We need to understand these challenges to be able to create an impactful, radical solution to create a #paradigm_shift_in_Arabic_education.