More than a decade ago, when I was in charge of the strategy and policy units under Prime Minister Tony Blair, I lamented to a friend that some of the policies simply weren’t working. The government had no shortage of educational policies. But the ones aiming to re-engage disengaged teenagers showed little sign of any impact. My friend asked me a simple question: looking back at my childhood, when had I learned most and why?

I had often done well academically. But to my surprise what came to mind were not the many hours spent in classrooms, but rather experiences like being stuck on a mountain in a blizzard with failing light, or working with a community group to clear some derelict land. These were the moments when I had learned profound new insights. In each case, my lessons had been gained because I had had to solve a real world problem, with others, and with something at stake.

It didn’t take long to notice that all of these features were roughly opposite in spirit to the policies we were implementing, and also opposite in spirit to the usual ways in which learning happens in schools and universities.

Of course my epiphany was hardly unique, and many others over the years came to very similar conclusions. But ever since I have been interested in how to integrate these lessons into the daily practice of schools and colleges, as well as my current work as an investor and funder, and to see how they can provide answer to the triple challenge of achieving better education, greater social mobility and higher productivity.

It should be almost self-evident that education fuels economic growth. The latest analyses of the origins of the industrial revolution show that it followed on from two centuries of dramatic improvements in literacy from around 10% to 50%, which probably played a bigger role than anything else in making it possible to mechanise and industrialise. More recently many nations have moved into the first rank of economies in large part thanks to heavy investment in education, from Germany in the 19th century, to Korea and Singapore in the late 20th century.

But it’s less clear what kinds of education really have the best effects. More isn’t obviously better, and there are plenty of examples of countries that invested heavily in education but didn’t win an economic dividend. So it matters to understand what really works and why, and how the complex needs of a modern economy made up of rocket scientists and farmers, computer scientists and cleaners, really connect to what happens within educational institutions.

A good starting point is to talk to employers. In many countries informal conversations with employers and formal surveys show similar patterns. Employers certainly value good literacy, maths and science. For many jobs it’s vital to have depth of knowledge, whether the job is in medicine or construction. But employers place even more weight on such things as motivation, resilience, communication and team work, and often lament how little schools do to inculcate these characteristics. These skills are of course learned more through experience than through formal pedagogy; through working with others rather than alone; and through solving problems in the real world rather than just on paper. A similar finding comes from academic research, including the work of Nobel Prize Winner James Heckman who showed that non-cognitive skills matters as much, if not more, than cognitive skills in explaining how well people do in life and in work. All of this might seem obvious. Yet remarkably few curriculums taught around the world take much notice of these points.

Any school or school system worth its salt should be consciously shaping its work to prepare young people to meet the needs of the wider society and economy, and not just the needs articulated by the education system itself. One answer which I’ve been closely involved in is the creation of ‘studio schools’, which organise most of the curriculum through practical projects, done in teams and with the close involvement of business, a model that deliberately synthesised dozens of good approaches from around the world, as well as the traditions of artists studios. There are nearly 50 studio schools in the UK and new ones opening in Brazil and other countries. All put non-cognitive skills at the heart of the curriculum, so that children learn how to be creative and how to cultivate their emotional intelligence and resilience, alongside history or physics. Teenagers learn by doing as well as through formal pedagogy, and each pupil has a personal coach to help them tailor their own learning. The result is that by the time the pupils leave school or university they are fully prepared to be useful members of the workforce – able to take initiative, to solve problems and to collaborate with others. The schools aim, in other words, is to inculcate agency.

Studio schools are only one answer, and similar models can be found in many countries, from Turkey to the US and India. But they are the exception not the rule, and tend to struggle with the pressures coming from policy-makers who are fixated only on the sorts of things measured by the OECD PISA scores.

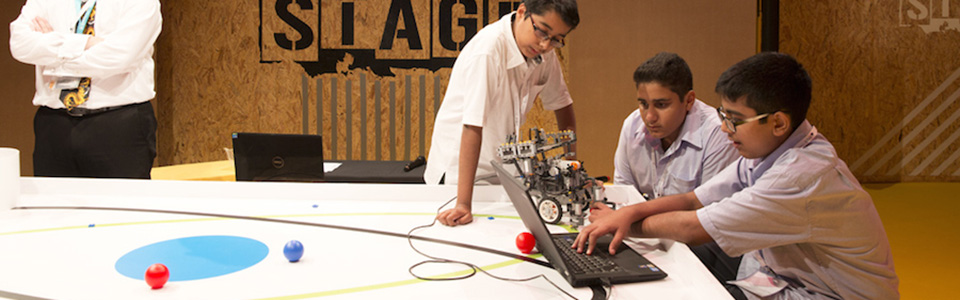

A related trend, and a similar challenge to educational orthodoxy, involves giving young people opportunities to be digital makers – to code, programme and create websites or apps, robots or games – rather than just being passive users of technology created by others. There are lots of good examples of schemes to do this from Estonia to India, as well as the UK’s Digital Making work that’s been given a great boost this year from the engagement of the BBC. Nearly always these programmes have had to recruit large numbers of volunteers to supplement teachers; and nearly always they have combined online tools and materials with face to face groups. Again a primary goal is to inculcate a sense of agency, of being ready to shape the world not just to consume or observe.

Initiatives of this kind should be emerging organically from within existing educational systems. But often they need the insights and energy of outsiders. Often, too, they need new kinds of capital. At Nesta we run investment funds that try to combine financial returns and educational ones in backing radical innovations that have the potential for significant impact. Recent examples include ventures developing new methods for digital assessment, adaptive learning or linking young people to apprenticeships. We’re part of a much larger global social investment movement that has seen the emergence of new banks, like the $1bn Big Society Capital, hundreds of social investment funds, as well as new asset classes like social impact bonds, that allow governments to pay only for outcomes achieved rather than inputs (for example rewarding success in helping poor teenagers complete schooling at 18).

This is still a nascent field. But it has the potential to transform how innovations in education and other fields are funded. It brings the benefits of an investment mindset that looks more rigorously at the causal links between action and outcomes (and, thankfully, tends to avoids the waste and indulgence that is also too often a characteristic of the investment industry). And social investment can promote more serious attention to evidence.

This last point is vital. It’s still remarkable how little evidence is used in education. Formal experiments remain very rare; and many practitioners in many countries make no use of what is known about what does or doesn’t work. Instead ideas spread from anecdote, or because of a good TED talk, not because they work in the real world. Ironically the Edtech world is worst of all, combining great promise with doubtful claims and very little serious independent evaluation. To fill these gaps the UK has created a ‘what works’ centre that provides teachers with easily digested guidance on the evidence for classroom practice. Various initiatives are under development to provide better evidence on what technologies really do achieve what they claim to achieve. And many new data tools are emerging to give feedback and guidance (such as the Studio Schools comprehensive assessment of non-cognitive skills, or websites using big data to show teenagers how their subject choices are likely to translate into jobs).

Evidence; investment; new ways of developing confidence and resilience; smart technologies: many of the elements needed for truly effective 21st century educational systems are available, and ready to be used to achieve the holy grail of combining better productivity, education and social mobility. But it will take courage to act on them and courage to remember very old insights about learning which we seem, repeatedly, to forget.