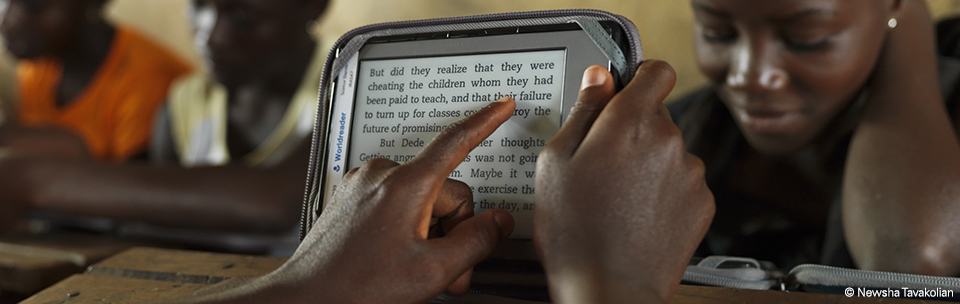

Stacked amidst temporary shelters, tents and thatched huts in Burundi’s Kavumu refugee camp are a pile of bright blue, green and yellow boxes. Stowed away in these 800 kg metal palette-size boxes are countless ideas to educate, entertain and foster creativity among refugees. The self-contained watertight boxes are packed with e-readers, tablets, cameras, e-books, paperbacks, board games and e-learning tools to offer educational and training opportunities to refugee children and adults and prepare them to reintegrate the world. In less than 20 minutes, the boxes are unfolded into interactive media centres with tables and chairs.

The Ideas Box is an out-of-the-box creation by the France-based Libraries Without Borders and has helped nearly 24,000 users in Burundi’s refugee camps.

What’s also unique about Ideas Box is the way it is being scaled up from refugee camps in Burundi or Jordan to address learning needs in entirely new settings and contexts: marginalised communities living in France, US and Australia.

Technology plays a big role to help solve education challenges such as access, quality and inclusion. When we think of education technology, we often imagine large-scale impact and reach.

But it’s not that straightforward. Very often, individuals and organisations launch an ed-tech project to address a specific challenge in a particular context. Once the project is a success, there is an urge to replicate it in other regions. But in many cases, plans fail.

“Given the size of many challenges we have in education around the world, thinking about scale is absolutely critical,” says Michael Trucano, senior ICT and education specialist at the World Bank. “A lot can be learned from the technology sector about innovating at scale. But when people come to education from the technology sector and see purely technical problems for which they design technical solutions, the results may not always work terribly well,” he adds.

So what are the main ingredients to scale up an ed-tech project from one context and culture to another?

“When organisations step into entirely new settings, flying solo is a big no! We need the local stakeholders. “There are two key elements to growing your footprint internationally in the education technology space: a) having educators on your side and b) having local credibility and expertise – especially when you are an outsider,” says Iris Lapinski. CEO, CDI Apps for Good, an organisation that equips students to create apps to solve social challenges.

Local educators, teachers, partners and staff can help better understand the context and ground realities to match users’ needs. When it comes to users’ needs, content comes first. What works for refugee children in Jordan may not necessarily serve the interests of those living in the Bronx. Or even if we narrow down the scope to a country, what works in one state may not necessarily work in another.

For instance, EverFi offers online financial literacy courses in North America, where school structures, funding models and curriculum vary from state to state. Everfi leverages a ‘ground game’ wherein the solution is sold to top decision-makers but the operational focus is on teachers and students. The team meets with teachers regularly to better understand specific needs and design classroom activities, benefitting nearly 12 million students across the continent.

For steady progress and large-scale impact, we need the right investors and partners who can support the expansion and implementation of the strategy. Lapinski says her organisation has failed to find strategic growth investors despite a six-month long targeted research. Lack of consensus on the long-term strategy and vision often end up being obstacles in the scaling process.

According to Trucano, “When scaling is seen only from the perspective of a technologist, there is often a lack of understanding of the human context and the on-the-ground realities of education,” To succeed, it is important to find investors and partners who understand the education sector, the context and stakes, and believe in the cause.

So once we’ve found the local support, tailored content to context and found the right funding – what’s left? Quality. For Jeremy Lachal, co-founder of Libraries Without Borders, “The overarching goal (and challenge) is to maintain the quality of the project as we scale up – be it in a refugee camp or in a poor neighbourhood in the French suburbs.”

Like Ideas Box, Bridge International Academies (BIA) is another ideal example of successful scaling. While low-cost private school chains are common, few match BIA’s scale, centralisation of activities, and ease of replication. To ensure quality, the program offers standardised, yet customisable instruction that can be easily replicated in new locations in emerging countries.

For founders Shannon May and Jay Kimmelman, scaling at a low pace was never an option. From the very onset, they kept in mind their mission to educate half a million children by 2017. The ‘Academy in a Box’ leverages technology, big data and a scale-driven approach to provide primary education at $6 per child per month.

There is indeed no straightforward strategy to scale an ed-tech project’s impact and reach. There will always be obstacles, failures and minor setbacks but one thing is for sure: one size does not fit all.

This article originally appeared on Forbes.