Sichuan province’s capital Chengdu is a sprawling flat city of ten million ringed in by misty mountains and lotus blossom ponds. It is a two and a half hour flight southwest of Beijing, and it sits on the edge of Chinese civilization, the entry point into the mystic mountains of Tibet and beyond. For thousands of years, Chinese have been venturing here to seek a spiritual awakening and be found, or to escape the repression and chaos of China’s coastal cities and be forgotten. Here, people love to eat “hot pot,” dumping fresh meat and vegetables into a spicy boiling broth; the city itself is a hot pot of cultures and religions, ideas and attitudes all mixing together. There is a vibrant gay nightlife, a dynamic art scene, a thriving IT sector, a cluster of famous universities, and a large community of political dissidents; in the lush outskirts, underground Christian schools, Waldorf kindergartens, and private Confucian academies are friendly neighbors. Chengdu is China’s idea of California, and that’s why the city today is the national leader in education innovation.

In mid-May, I spent a week in Chengdu, visiting a variety of schools and researching how they innovate. What I discovered is that in Chengdu there are three types of individuals who work together to drive innovation: the pioneering radicals who experiment with new ideas and approaches, the garrulous connectors who take everyone out for a long slow dinner of hot pot, and the savvy practitioners who adopt and adapt new ideas into the mainstream.

I first visited the three-year old private Pioneer School, where the charismatic thirty-year old vice-principal Cui Tao showed me around the sun-soaked and fragrant campus of brownstone buildings, manicured lawns, and luxury apartments. The campus was built to be a business school, and when that failed the Pioneer School turned it into a hippie enclave. There’s no curriculum and few rules, and students were free to learn whatever they wanted whenever they wanted however they wanted, with teachers acting as mentors and facilitators. The school’s philosophy and pedagogy were similar to that of many successful Western education experiments, including the Sudbury Valley School, the Summerhill School, and Hampshire College.

What’s different was that most of the school’s forty teenagers had flunked out of China’s test-centered public school system, which left them traumatized and withdrawn. When Cui Tao and I walked into a dorm room at lunchtime, one student was playing Minecraft in the living room, and everyone else was still asleep. In fact, that’s really how most of the students spend their time at Pioneer – either asleep or playing video games.

“Here, we don’t believe in discipline or control,” Cui Tao told me in his soft calm voice, as I scanned the garbage-strewn apartment. “Kids become addicted to video games when it’s their only way to assert their individuality in a system that demands their total obedience. So, here, we believe in listening to our students, respecting their choices, and appreciating their individuality.”

What this meant in practice was that Cui Tao and his students spent a lot of time playing videogames together. “Anything is a learning opportunity,” Cui Tao told me. “To master anything, you have to keep focus, work hard, and push yourself.” Turning video games into a learning challenge meant that once students mastered playing video games, they got bored, and sought a new challenge. I talked to one seventeen-year-old who had played video games for two years, but was now entirely committed to reading and learning.

“Here, we have space to make mistakes, and time to reflect on our mistakes,” the student told me. “That makes us better human beings. I used to fight with my mother all the time. Now I can see things from her perspective, and we can now reason out our differences.”

Every week, Cui Tao arranged for everyone to read a book together, and right now they were reading Peter Gray’s Free to Learn. As I flipped through it, I found the passage that best articulated Pioneer School’s philosophy:

Play is nature’s way of teaching children how to solve their own problems, control their impulses, modulate their emotions, see from others’ perspectives, negotiate differences, and get along with others as equals. There is no substitute for play as a means of learning these skills. They can’t be taught in school. For life in the real world, these lessons of personal responsibility, self-control, and sociability are far more important than any lessons that can be taught in school.

In the evening, Cui Tao invited me to a hot pot meal with an education magazine editor Li Yulong.

As large and as garrulous as Falstaff, Li Yulong knew everyone who was anyone in Chinese education. In his mid-fifties, wearing shorts and sandals, Yulong had a restless energy to him, and his curiosity was as his boundless as his appetite. He’s Chengdu education’s diplomat and connector, traveling far and wide across China, swallowing anything that interested him and embracing anyone who shared his passion for education innovation. He became my local guide, and over the week he arranged for me to visit a variety of schools.

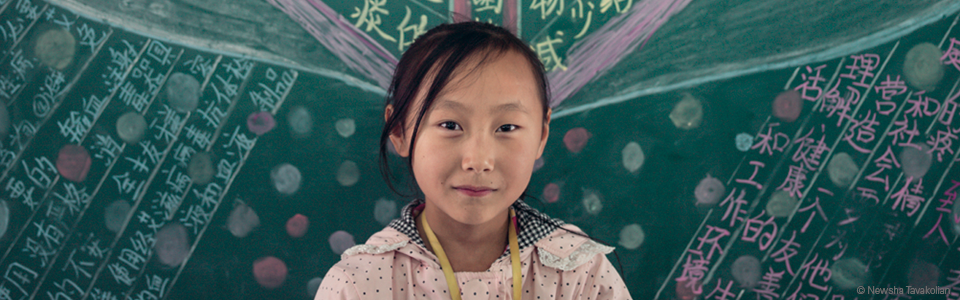

One school I visited was Tonghui Elementary School, where Li Yong had been principal for three years. He’s a soft-spoken forty-two year old with bushy eyebrows. He told me that Yulong had a profound influence on him, and remained a constant source of inspiration. Twelve years ago, as an “angry young” (fenqing) teacher, Li Yong met Yulong online, and the two became fast friends. Yulong arranged for Li Yong to visit Chengdu’s Waldorf School, and inspired Li Yong to teach his elementary school students to analyze and criticize the history textbooks that they were reading together.

As we toured Tonghui, Principal Li was visibly proud of how he had adapted Waldorf practices into his public school of 1,200 students. On the top of his gymnasium there’s an organic farm. There were carpentry and pottery classrooms, and in every class there’s a lot of lively back-and-forth discussion between teachers and students.

“But how did you achieve this in a normal public school?” I asked Principal Li.

He smiled, and laughed. “Patience,” he told me. “A lot of patience.”

In order to reinvigorate an old system with new ideas, Principal Li had to build from scratch the democratic systems and processes that would permit new ideas to take root and flourish. He spent a whole year negotiating with his teachers on new teaching performance protocols. “The point wasn’t for me to impose my ideas on the teachers,” Principal Li told me. “The point was to create a culture of openness, transparency, and mutual respect.” He wrote a weekly letter to parents, and every Saturday morning parents came to study alongside their kids. This culture meant that Principal Li could introduce innovations such as “Get Dirty” days, in which kids rolled around in the mud for a day.

To conclude my visit to Tonghui, Principal Li arranged for me to have an hour-long round-table discussion with twenty kids from the fifth and sixth grades – which was something I’ve never experienced in any school before. The kids were open and friendly, and they vocally but politely argued against each other.

“Here, teachers don’t give too much homework,” I said. “Aren’t you worried that you’re not learning as much as students in other schools?”

“Teachers should be able to teach all the material in class,” one girl said. “If they give too much homework, it’s because they’re terrible teachers.” There were a couple of teachers sitting in the back, and they snickered.

“It’s important we have time to think for ourselves,” a boy chipped in. “That’s the only way we can grow as individuals.”

We had the round-table in the pottery classroom, and a class of third-graders was only a few feet from us doing their pottery projects. They made no noise, and when their class was over they crept out of the classroom so as to not disturb us. I pointed this out to the students.

“Why are students here so polite and well-behaved?” I asked them.

“It’s because we have a culture of mutual respect,” a boy told me. “We didn’t disturb them, and so they didn’t want to disturb us.”

Everyone nodded in agreement.

Jiang Xueqin is a China-based writer and educator. He tweets at @xueqinjiang.

Jiang Xueqin was a speaker at WISE 2014. Watch his session: Empowering Teachers for Creativity.

Read the other articles in the series: Are Creativity and Innovation Possible in Chinese Schools; The China Education Debate: Equity Versus Excellence; The Pioneer Way: Emotional Scaffolding; The Xingwei Experiment; The Secret to School Transformation: Emotional Plumbing